On January 17 at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Chinese President Xi Jinping urged all signatories to "stick to" the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. Here's my take on how Germany, China, Japan and subnational jurisdictions may actually keep a strong pace of progress on the Paris Agreement - even though the loss of global consensus in this area will take the pressure of fast-industrializing countries like India and Vietnam to speed up their transitions from coal to clean energy, resulting in a faster pace of global warming. This is an abridged version of an article written for Oxford Analytica, who own the copyright.

Global elites meeting in Davos this week witnessed the unusual site of a Chinese president being greeted as the world's pre-eminent champion of free trade and action on climate change. President Xi Jinping’s keynote speech sent a strong message that China will join efforts to sustain the Paris Agreement - in a year where its proposed launch of a national carbon market could be a major breakthrough for global CO2 reduction.

'G2' cooperation. China's current embrace of international climate cooperation -- an issue that saw negligible traction in Beijing as recently as the early 2000s -- marks a rapid shift, motivated in part by concerns for social stability.

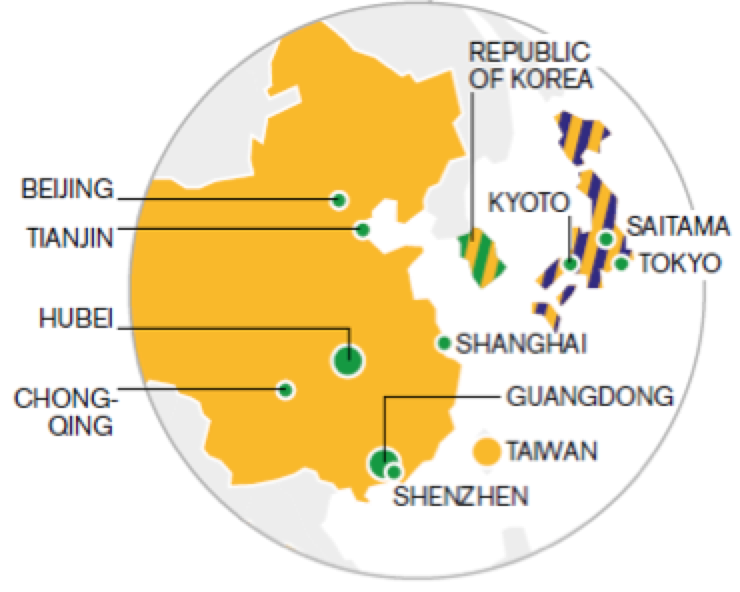

Discontent over air pollution, together with the likely impact of high CO2 scenarios for China's crop productivity and water scarcity, helped prompt ambitious measures under the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2006-2010) and Premier Li Keqiang’s declaration of a “war on pollution.” Xi redoubled this momentum by supporting pilot schemes to price CO2 emissions in Shanghai, Shenzhen and major economic centers, culminating in his announcement that China will launch a national carbon market in 2017 -- a measure that would raise the share of global GDP subject to carbon pricing from 13% to 25% at a stroke.

As it built a program of action on climate change, China benefited from an intensive dialogue with US counterparts that sought to avoid 'prisoner's dilemma' outcomes in which the world's two largest emitters would suffer environmental consequences should either one of choose a "do nothing" strategy. US officials credit the so-called 'G2' talks with coaxing China into assuming global responsibilities under the Paris Agreement: a decisive shift from the Kyoto Protocol, which placed obligations only on developed countries. China pledged to peak its emissions by 2030, while the United States passed the Clean Power Plan, which now faces repeal.

German G20 presidency. Germany assumed the presidency of the G20 just three weeks after the US presidential election with the declared goal of "opposing isolationism and strengthening international cooperation". The G20 presidency is one of several ways in which Berlin may have significant influence during 2017:

- Germany will set the agenda for the G20 Leaders Summit, scheduled for July 7-8 in Hamburg, where Trump will encounter the leaders of the European Union, Canada, India, Japan, Australia, Russia, and other G20 leaders. In a deliberate nod to populist trends, President Duterte of the Philippines is invited as a guest participant.

- Given its highly favorable fiscal position, Germany is being relied on for an intended capital increase of the World Bank's largest lending arm, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Berlin's generosity towards multilateral institutions will be the lynchpin for any deal to preserve their financial capability - which is currently dwindling - and the support could potentially be linked to climate change measures in middle-income countries.

Current political trends suggest that a shift in Germany's environmental stance is unlikely. Merkel faces rising pressure from the Alternative fur Deutschland (AFD) as she seeks a fourth term, yet the party's populist is premised on anti-migrant sentiments and it does not challenge green politics. Following a well-received speech in which she explicitly conditioned Germany's engagement with the new US administration on "shared values" being upheld, her stance towards the unorthodox new president could benefit her chances in the late 2017 general election.

Subnational networks. Governor of California Jerry Brown pledged in December that Trump's election will not slow climate action in the state, where Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton won 61.5% of the vote.

Sub-national jurisdictions have several opportunities to advance the Paris Agreement goals:

- California has instituted a cap-and-trade emissions pricing system and linked this to Quebec's scheme. Subnational jurisdictions, of which 20 currently operate a carbon price, have much scope to drive forward market mechanisms that reduce CO2 during the Trump administration years.

- California exemplifies the market power of a large sub-national jurisdiction with authority to regulate product standards. Ambitious municipal targets for electric car adoption could drive significant CO2 mitigation by supporting a transformative technology.

US and Canadian states and provinces are likely to step up direct cooperation with developing country governments, picking up some slack left by reduced US federal government action. Moreover, US states may implement the expected boost in infrastructure spending to adapt their transport systems to climate change - a theme that increasing shapes infrastructure asset management plans of states such as Florida and Colorado.

China's carbon pricing schemes in major cities (green) may soon be joined by a nationwide carbon market (yellow) - in theory raising the share of global GDP under a carbon price from 13% to 26%. Source: 2016 Carbon Pricing Report.

Resilient legal form. The Paris Agreement itself was carefully structured to minimize the likelihood and consequences of rejection by an incoming US Republican administration in the United States. Should the administration adopt a hostile stance to the agreement, consequences could include:

- refusing to participate in the 2018 ‘stocktake’ and 2023 five-year review of national efforts;

- opposing strong implementation of the Paris Agreement’s Article 6 on international carbon markets;

- submitting no national action plan (‘Nationally Determined Contribution’) or a weak one; and

- weakening the ‘Paris rulebook’ which will operationalize key provisions on transparency and verification of national emissions accounting.

In addition, the US administration will almost certainly cancel 2.5 billion dollars promised by its predecessor to the Green Climate Fund.

Chilling effect. While the Paris Agreement machinery is likely to survive a hostile US administration, the substance of cooperation on climate change will be more severely affected by the likely weakening of US ambition for emissions reduction. On aggregate, US emissions may continue to follow the encouraging trend driven by a changing energy mix driven by natural gas exploitation. However, policy-driven CO2 reduction will certainly be less ambitious.

The weakening US policy chance on energy and the environment may have a significant demonstration effect in countries whose emissions trajectory will have greatest global impact in coming decades – potentially slowing the transition from coal in India or Vietnam, or dissuading countries such as Mexico from adopting carbon prices. Intensified cooperation through bilateral aid programs and international financial organizations could help mitigate this trend, especially if accompanied by concessional funds to help speed energy transitions that require up-front investment.

Forthcoming Board discussions at the Beijing-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank will be important in deciding whether this new institution adopts an ambitious clean change and clean energy mandate – in if so it could play a significant role in deepening progress on resilience and energy transitions in Asia, bringing additional financial muscle alongside existing institutions such as the World Bank and Asian Development Bank.